In an era marked by rapid technological change and global interconnection, a powerful economic paradigm has quietly reshaped how wealth accumulates. We now live in a world where income increasingly stems from owning and controlling scarce assets rather than generating value through labor or productive ventures. Understanding this shift is crucial for individuals, policymakers, and societies seeking to foster fair growth and lasting prosperity.

At the heart of this transformation lies the concept of economic rent: earnings above what is needed to bring a resource into productive use. When a growing share of income derives from this rent—rather than from selling one’s labor or investing in innovation—we call the resulting order a rentier economy.

Understanding the Rentier Economy

A rentier economy is one where wealth creation centers on collecting rents from assets already in place instead of expanding productive capacity. This model contrasts sharply with a classical industrial economy, in which profits arise from reinvestment in tools, factories, and human capital.

Key distinctions to grasp:

- Capitalist profit depends on organizing production, exploiting wage labor, and reinvesting to gain efficiencies.

- Rentier profit flows from controlling scarce assets—land, minerals, credits, platforms—and charging others for access without a compulsion to enhance productivity.

John Maynard Keynes famously labeled rentiers as “functionless investors who earn income” through ownership rather than contribution. This phrase captures the disconnect between rent-based earnings and the creation of new goods, services, or employment.

A Historical Journey

The roots of this phenomenon trace back to classical political economy. Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill identified landlords and monopolists as rentiers, capturing unearned income through scarcity and legal privilege.

John Stuart Mill lamented that some individuals could “make money in their sleep,” emphasizing rent as a mere transfer payment divorced from production. The industrial era that followed aimed to minimize rents and unnecessary production costs, freeing markets to reward productivity and innovation.

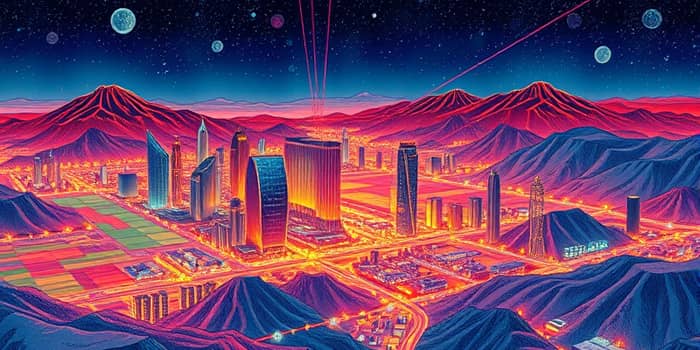

Yet, since the 1970s, a seismic shift occurred. Finance, real estate, and technology platforms began to eclipse manufacturing. As global capital liberalized, deregulation and privatization expanded opportunities for rent extraction. Michael Hudson and others argue that today, interest, rents, and dividends yield more income in advanced economies than industrial output.

Rentier States and Rentier Capitalism

Rentier dynamics operate at both national and corporate levels. Understanding these two forms reveals how pervasive the trend has become.

Rentier States

A rentier state depends heavily on external rents—such as oil, gas, or mineral exports—to fund government budgets rather than citizen taxation. This undermines accountability, weakens productive sectors, and fosters patronage systems.

- External rent dependence from commodities like oil or gas.

- Limited diversification, with underdeveloped manufacturing and agriculture.

- Subsidies and public-sector employment funded by resource revenues.

- Weakened link between taxation and representation, reducing transparency.

Classic examples include Gulf oil monarchies, Nigeria, and other resource-rich nations, where cycles of boom and bust reinforce authoritarian tendencies.

Rentier Capitalism

In advanced economies, rentier capitalism describes firms and individuals earning disproportionate income from asset control rather than entrepreneurial risk-taking. UNCTAD defines rent as earnings from ownership alone, not from innovation or value creation.

- Finance: banks and funds profiting from interest, fees, and trading gains.

- Real estate: landlords capturing rising property values and rents.

- Infrastructure: privatized utilities charging monopoly prices.

- Big Tech platforms: leveraging network effects, data control, and digital chokepoints.

Mechanisms of Rent Extraction

How does living off assets work in practice? Rent extraction takes many forms—each undermining productive investment and distorting markets.

Consider land and real estate. Classic rent emerges when landlords charge tenants for access to a finite resource: location. Modern tax preferences for property further inflate prices, forcing households to allocate more income to mortgages and rents.

Natural resources—from oil fields to mineral deposits—generate windfall profits for those who own extraction rights. When these rents are recycled into consumption or patronage rather than innovation, nations lock in a dependency that erodes long-term resilience.

Financialization extends rentier logic to money itself. Banks and creditors control the scarce resource of credit, earning interest and fees on mortgages, student loans, and consumer debt. As credit inflates asset prices, households find their earnings drained by debt servicing.

As rent extraction becomes more lucrative than producing goods and services, societies face rising inequality, volatile markets, and weakened democratic accountability. Wealth concentrates in a small class that lives off pre-existing assets, shaping laws and policies to protect their privileges.

Charting a Path Forward

Fortunately, awareness is the first step toward change. By diagnosing the rise of the rentier economy, individuals and communities can pursue strategies to reinvigorate productive growth and ensure fairer outcomes.

- Promote progressive taxation on unearned income—rents, dividends, and capital gains.

- Invest in public infrastructure and R&D to expand productive capacity and reduce dependency on private monopolies.

- Strengthen antitrust enforcement to dismantle chokepoints in technology, finance, and utilities.

- Support cooperative and community-owned models for land, housing, and essential services.

By redirecting resources toward genuine innovation and labor-driven enterprise, we can reclaim an economy that rewards effort and creativity. This vision calls for solidarity, bold policymaking, and a cultural shift that values contribution over ownership alone.

The rentier economy may be a dominant force today, but it is not destiny. Empowered citizens, informed voters, and enlightened leaders can reshape markets to serve the many rather than the few. Together, we can build a future where prosperity springs from human ingenuity, not legal privilege.

References

- https://energy.sustainability-directory.com/term/rentier-state-dynamics/

- https://www.prindleinstitute.org/2019/03/what-is-rentier-capitalism/

- https://michael-hudson.com/2025/10/gdp-without-goods-the-rentier-mirage/

- https://legal-resources.uslegalforms.com/r/rentier-state

- https://academic.oup.com/cje/article/47/3/507/7160981

- https://c4ss.org/content/59416

- https://substack.com/home/post/p-151199875

- https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/blog/can-rentier-capitalism-explain-big-tech/

- https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2011/02/15/america-from-progressive-to-rentier/

- https://unctad.org/news/rentiers-are-here